My mindframe as I walked into the Frida Kahlo exhibition was sceptical interest. I’d read reviews by blokes that were

negative and reviews by blokes that were positive. And I was well aware of Kahlo’s status as a feminist icon, who had a fascinating, traumatic life. But ultimately, you can only judge an artist by their art.

And it was Kahlo’s art that caused me to leave the exhibition shaken, almost overwhelmed, and convinced that she deserves to be up there as one of the greats. One day an exhibition will establish this beyond doubt; this is not, however, that exhibition – it merely points towards that possibility.

The Tate show focuses too much on her early art, and her political art, which is, it must be admitted, rather thin, and sometimes undergraduate. The mocking of America in My Dress Hangs There (1933), which features a golf trophy and a toilet on matching monumental columns is mildly amusing, but it isn’t great art. Her political paintings, while adding to the understanding of her life – her involvement with the nationalist Mexicanidad movement and marriage to a leading member of that movement – do little to advertise her art.

The first painting in this exhibition that stopped me was, however, very early in her career. A Few Small Pricks (1935)is based on a newspaper account of a brutal murder, in which a man who’d stabbed his lover with a knife many times said: “I gave her only a few little pricks.” Enclosed in a simple wooden frame covered too with the “blood” of the scene, Kahlo presents its simply, realistically. There is absolutely no dignity, no glamour in this death: an early sign of an absolutely uncompromising artistic vision.

Even earlier, another central aspect of her art – its personal nature – is evident in My Birth, painted after Kahlo had suffered a traumatic miscarriage and her mother had died. She emerges in gynaecological detail, but her mother’s face is shrouded like that of a corpse in a sheet, and the body/mother lies in a bleak, empty room, albeit it on perfectly made bed. This, with its Marian icon above the bed, must have been truly shocking in the Mexico of 1932.

But in this show you are then sent through several rather thin rooms of political art, drawings and still lifes (for which what I’d suggest over-grand claims are made – although the dreadfully kitsch circular flower painting, made for an American actress with whom her husband is thought to have been having an affair, is an enjoyable joke).

It is in the next two rooms that Kahlo’s greatness emerges. It is no accident that nearly all of the paintings are self-portraits in one form or another: it is when Kahlo is in her body, or out of her body looking in, that she’s at her most powerful. She makes the personal into art long before feminists came to call it political.

My single favourite, if I had to pick one, is Self-portait with Monkeys (1943). Kahlo, with a typically studiously neutral expression, wearing a simply white shift, stands amidst but apart from luxuriant tropical foliage, accompanied by these four primates. Two, diffidently and uncertainly, look as though they are trying to comfort her; the other two are curious onlookers. As a restrained portrait of sad, but proud, solitude and alienation it is breathtaking.

Yet Kahlo is not always so restrained. Self-Portrait with Loose Hair (1947) is more obviously, emotionally, bleak, as is The Mask (1945), in which Kahlo conceals her face behind a papier-mache image of La Malinche, the Indian mistress of the conquistador Cortes.

But it is when Kahlo maintains her distance that she is at her most powerful. That’s again the stance in The Little Hart (1946)in which Khalo is a stag in a forest pierced with a flurry of arrows, yet her face looks out at us serene, groomed, detached.

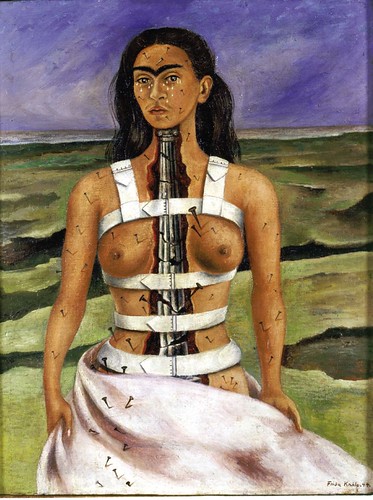

That neutral expression becomes strained, however, in The Broken Column (above). Painted in 1944, it reflects the continuing deterioration of her already shattered body. It is a depiction of shattering, chronic, inescapable pain and suffering that refuses to slide into self-pity.

Kahlo is, perhaps inescapably in view of the framework of her life, chiefly a painter of the miserable side of the human condition. But she rises above that, to show that even in misery there can be dignity and nobility. And she shows that from the perspective of the human body – the female body. Can you really claim – as some continue to do – that this in any way invalidates her greatness, rather than amplifies it?

The exhibition is at the Tate Modern until October 9.

This is a good collection of resources about Kahlo.

About

About

One comment

Pingback: My London Your London » Theatre Review: Frida Kahlo, Viva La Vida at the Oval Theatre, South London