.flickr-photo { border: solid 2px #000000; }.flickr-yourcomment { }.flickr-frame { text-align: left; padding: 3px; }.flickr-caption { font-size: 0.8em; margin-top: 0px; }

An impulse purchase at the London Review of Books bookshop turned out well.

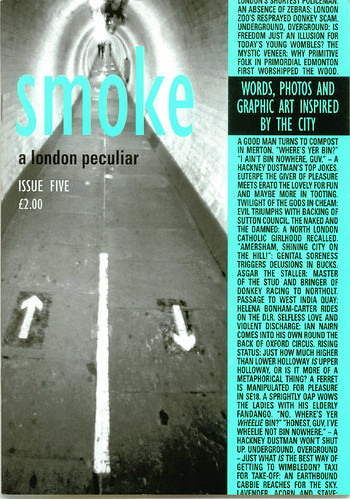

This little publication is packed with articles, stories and pictures of the less-fashionable parts of London and interesting facts, surprisingly well edited and put together*.

The contents of Smoke: a london peculiar include

* a history of elephants in London – the first was in 1255, a present from Louis IX to Henry III.

* “Rodent Rovings” – in Philpot Lane there is apparently a 19th-century building bearing a carving of two mice nibbling cheese – apparently a builders’ initiative to commemorate the plague they had to work through. (Have to go looking for that.)

* There’s a warehouse of the north circular between Walthamstow and Edmonton that has a regularly changed feature “Veneer of the Week”. Apparently there’s 70 to circulate among.(I used to drive this road quite often, but never noticed this “feature”.)

* I learnt about Northolt, on one of the ends of the Central Line: “It’s not even a non-place, to use Auge’s term, just a bus stop on the way to Heathrow. Northolt has good company in the excised remains of the county of Middlesex, though. JG Ballard’s Shepparton is on the other side of the airport catchment area and somewhere in the Enfield enclave is a place called Ponders End, from where Norman Tebbitt hails. And I’m sure Stevie Smith was talking about Northolt when she made the jibe about what Town Hall terms “greater metropolitan areas” being all sub and no urb. It is enough to make Henri Lefebvre weep into the lap of one of his secretaries.” (From “Flight Paths”, Paul Castro)

********************

*No I don’t know the editors, nor am I being paid by them.

More here.

About

About