A shorter version was first published on Blogcritics

I last really looked at Pterosaurs some 30 years ago, when as a fossil-obsessed young teen, I haunted the paleontology section of the Australian Museum in Sydney. After reading Mark P. Witton’s new Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy I now know that practically everything the displays told me about pterosaurs, that they were incredibly light, fragile, clumsy creatures, walking on two legs, primitive in their evolutionary conception, were, while the “wisdom” of the time, entirely wrong.

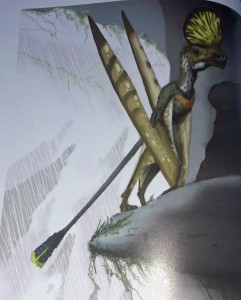

Pterosaurs is an unusual format – a coffee table-style book in its format, yet seriously academic, uncompromisingly serious in its content, except for an occasional whimsical light note, most commonly in the captions. To the right is, in Witton’s terms, is “one of the coolest-looking pterosaurs known”, Caviramus filisurensis. He also notes that “diddly-squat has been said in print about the biomechanics and functional biology of boreopterids“.

It’s unusual, but it works. I doubt too many non-academic readers will absorb every word about the anatomical morphology of ptesoaur types, or the long-running and often unresolved academic debates about the relative evolutionary relationships between different groups, but all the detail is there if you should want to dive in

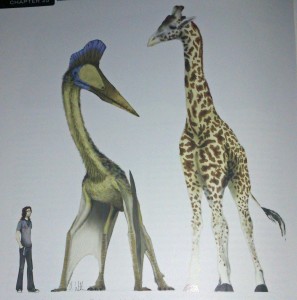

For those looking for the lighter version, there’s wonderful illustrations, also by Witton, of both reconstructions of pterosaurs in their environment, so far as we can know it, as well as a couple that help to put them in context, as with azhdarchid transposed with a human and a Masai giraffe right.

And the middle ground, in which I belong as a reader, to a whole exploration of the evolution, physique, physiology and ecology of this diverse, long-lived family that finally disappeared with the dinosaurs.

A lot of conventional wisdom is dispelled. Among the biggest surprises, that on the ground they were effective, often fast, movers, fully quadrupedal, that their bodies were primarily covered with a pelt of what are called pycnofibres, not scales or feathers, and that they aren’t dinosaurs, but belong to their own branch of the evolutionary tree, although whether that branches off before the Crurotarsi or after the Scleromochlus, or off earlier branches, is clearly a subject of much debate.

More, they were much heavier than had been predicted in studies of most of the last century, and not gliders or clumsy fliers, but every but as effective as the birds who eventually replaced in them in the skies. And they probably didn’t evolve from gliders, but from small, high energy little creatures (there’s a strong argument for the pterosaurs being warm-blooded – helping explain the pelt), running around trees or craggy cliffs. Further, the headcrests that are a prominent feature of some species are not, at least generally, either aerodynamic features, or temperature regulators, but competitive mating features, generally only found on the males, which suggests, with other evidence, that many were lek breeders, with males competing for the control of harems of females.

So there goes pretty well everything you thought you knew about pterosaurs, if you picked the knowledge up a couple of decades ago. That’s not surprising, for Witton begins with short survey of pterosaurology, which records that, for reasons not really explicable, from the 1930s to the 1970s, studies virtually stopped, so that he world’s first popular pterosaur books, Dragons of the Air, published in 1901, remained effectively the current state of knowledge.

read more

About

About