A shorter version was first published on Blogcritics

I last really looked at Pterosaurs some 30 years ago, when as a fossil-obsessed young teen, I haunted the paleontology section of the Australian Museum in Sydney. After reading Mark P. Witton’s new Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy I now know that practically everything the displays told me about pterosaurs, that they were incredibly light, fragile, clumsy creatures, walking on two legs, primitive in their evolutionary conception, were, while the “wisdom” of the time, entirely wrong.

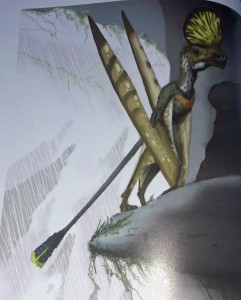

Pterosaurs is an unusual format – a coffee table-style book in its format, yet seriously academic, uncompromisingly serious in its content, except for an occasional whimsical light note, most commonly in the captions. To the right is, in Witton’s terms, is “one of the coolest-looking pterosaurs known”, Caviramus filisurensis. He also notes that “diddly-squat has been said in print about the biomechanics and functional biology of boreopterids“.

It’s unusual, but it works. I doubt too many non-academic readers will absorb every word about the anatomical morphology of ptesoaur types, or the long-running and often unresolved academic debates about the relative evolutionary relationships between different groups, but all the detail is there if you should want to dive in

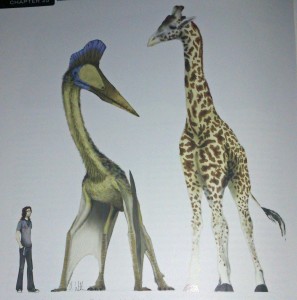

For those looking for the lighter version, there’s wonderful illustrations, also by Witton, of both reconstructions of pterosaurs in their environment, so far as we can know it, as well as a couple that help to put them in context, as with azhdarchid transposed with a human and a Masai giraffe right.

And the middle ground, in which I belong as a reader, to a whole exploration of the evolution, physique, physiology and ecology of this diverse, long-lived family that finally disappeared with the dinosaurs.

A lot of conventional wisdom is dispelled. Among the biggest surprises, that on the ground they were effective, often fast, movers, fully quadrupedal, that their bodies were primarily covered with a pelt of what are called pycnofibres, not scales or feathers, and that they aren’t dinosaurs, but belong to their own branch of the evolutionary tree, although whether that branches off before the Crurotarsi or after the Scleromochlus, or off earlier branches, is clearly a subject of much debate.

More, they were much heavier than had been predicted in studies of most of the last century, and not gliders or clumsy fliers, but every but as effective as the birds who eventually replaced in them in the skies. And they probably didn’t evolve from gliders, but from small, high energy little creatures (there’s a strong argument for the pterosaurs being warm-blooded – helping explain the pelt), running around trees or craggy cliffs. Further, the headcrests that are a prominent feature of some species are not, at least generally, either aerodynamic features, or temperature regulators, but competitive mating features, generally only found on the males, which suggests, with other evidence, that many were lek breeders, with males competing for the control of harems of females.

So there goes pretty well everything you thought you knew about pterosaurs, if you picked the knowledge up a couple of decades ago. That’s not surprising, for Witton begins with short survey of pterosaurology, which records that, for reasons not really explicable, from the 1930s to the 1970s, studies virtually stopped, so that he world’s first popular pterosaur books, Dragons of the Air, published in 1901, remained effectively the current state of knowledge.

There’s clearly been a huge leap forward since then, and some of the other illustrations in the book, pictures of fossils, including those using exotic forms of lighting that can sometimes reveal soft tissue features not visible under normal conditions, explain why.

The reader of Pterosaurs will also learn a great deal about the biology of the modern day. I was fascinated to learn that pneumatic bones, air-filled and supported by thin bony struts are not, as I’m sure I was taught at school, that way to make them “lightweight”. Bats reach fairly large wingspans without pneumatisation, and at the same body mass, bird skeletons are as heavy as those of mammals. I also learnt about cookiecutter sharks, around today (sorry if you have nightmares, you probably shouldn’t have read about them…)

For those who like their biology really detailed, there’s an exploration of what’s known about animal vomit. “Lizards, snakes and crocodilians digest most bones and only regularly vomit the most resilient, proteinaceous parts of their food (claw sheaths, hair, feathers and so on). Some birds also almost entirely digest bones but most regurgitate bones that have been lightly etched with acid during the digestive process.” The point of this in this context is that pellets found at Las Hoyas in a pterosaur context don’t fit either description, and probably came from a small dinosaur or pterosaur. Some pterosaurs swallowed food whole, through an extremely elastic esophagus, as demonstrated by an amazing photo of a late Jurassic fossil from Germany of a Rhamphorhynchus that had a complete swallowed fish in its bowels that occupies 60% of the torso length.

About half the book consists of an exploration of the pterosaurs as a group, the remainder being an exploration of the different groups. Among my favourites are the Anurognathidae, small but clearly nimble, powerful and quick moving beasts, which probably were rather like bats on feeding on insects on the wing. Their shape even suggests that while powerfully flapping and swooping, they would have been almost silent, and some fossils found suggest they would have lived in forests, when at rest tucked inconspicuously into nooks and cranies. (Witton suggests that the early pterosaurs can’t have been insect eaters – far too sophisticated flying skills are required.)

The work concludes, as you’d expect, with the “Fall of the Pterosaur Empire”, in Witton’s terms, which coincides with the end of the dinosaurs. Witton has little doubt that can be laid at the feet of “an enormous meteorite impact, extensive volcanic activity, and shifting climates in the last few million years of the Mesozoic all probably played some part”. But he’s more interested in the question of whether the pterosaurs were already in deep decline, maybe pushed out by birds. His conclusion is that by the end of Mesozoic the azhdarchids had come to dominate at the expense of all other type – although not because they bullied them out; there’s not enough evidence to give a reason. “Late Cretaceous pterosaur stock was almost entirely invested in one, slowly adapting lineage and was therefore very vulnerable.” It might have died out even without ecological catastrophe.

It seems a fair conclusion, and a credit to Witton that he’s prepared to admit lack of knowledge and evidence, as he does throughout the book. But perhaps the most memorable image is in this last chapter, simply labelled “the end”, a dying azhdarchid lying on a forest floor, its head wearily lifted from the snow, its body emaciated. A powerful image.

Other reviews: from Pterosaurs.net (well of course!), a critical review on The Pterosaurheresies, and on National Geographic.

About

About

3 Comments