.flickr-photo { border: solid 2px #000000; }.flickr-yourcomment { }.flickr-frame { text-align: left; padding: 3px; }.flickr-caption { font-size: 0.8em; margin-top: 0px; }

I think I’ve already found one of my books of 2005, The King’s Midwife: A History and Mystery of Madame du Coudray, by Nina Rattner Gelbart.

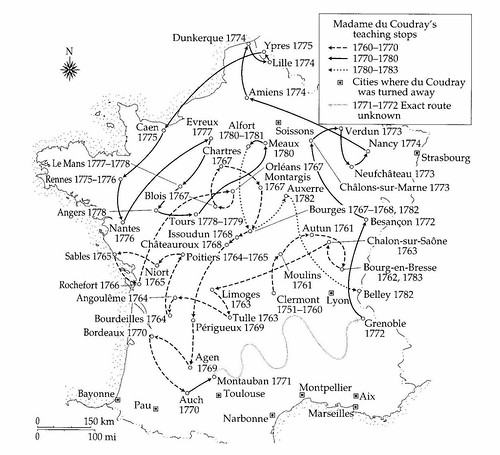

Above is the map assembled by the author (from ten years of research, primarily in French provincial archives) of the travels of Mme Coudray (1715-1794), who after more than a decade as a leading midwife in Paris move to the countryside and, seeing the horrific state of ignorance and mutilation of women and babies that was occurring decided to fix the situation.

Through skilled, persistent campaigning, she won support and funding from the king (and she had to keep fighting to retain it). She was utterly realistic about her work, developing a “machine” that modelled a baby and womb so that ill-educated or uneducated countrywomen could learn by feel what was needed in normal, or abnormal, births.

Unlike her contemporary in England Elizabeth Nihell, she was not explicitly feminist, prepared to work with and adapt to the surgeons and male midwives then trying to take over the profession (and educate them, when they were prepared to listen).

Having developed this programme, she then took it to all the parts of France that would accept her, as the above map indicates, at a time when it was customary to make a will before embarking on a journey, and the experience could only be described as an endurance test.

The effects she had can be illustrated from a survey in 1786 of medical services around the country. Of the 6,000 midwives whose answers survive (many have been lost), two-thirds had been trained by Mme du Coudray or one of the surgeons that she had trained in her method. (And she is the only trainer mentioned by name. p. 250)

Sadly, but perhaps inevitably, she was after all the “royal” midwife, she died in unknown circumstances while in the hands of the agents of the Revolution, but her “niece” (any blood relationship is unclear), Mme Coutanceau, who she had trained but who became more explicitly feminist, managed to carry on the work from Bordeaux, where she established and ran a birthing clinic that helped the poor and trained midwives.

(Almost nothing on the web: there’s a picture of the only surviving machine and reviews of the book here and here.)

About

About